As the National Digital Forum (NDF) finishes for another year, I find myself thinking of the past decade. And as we farewell the 10s for the much easier to pronounce 20s, I also think on what the future might hold.

How have we changed as a GLAM sector in the last 10 years, and how will we evolve? What new technologies await beyond the borders of our imagination? Who will be our audience, and why will they come? Curiosity, Anger, Obligation, Love? Will GLAM institutions even need to exist? And if so, will they still be talking about the same issues we face today or faced 100 years ago?

Many large scale digitisation projects have finished, and the results have been contemplative. Dave Sanderson (Auckland War Memorial Museum) provided a fascinating talk at NDF called “Digitise or Die”. As ominous as it sounds, he stressed that organisations no longer need to consider mass digitisation because that is what everyone else is doing. Digitisation needs to be thoughtful, it needs to have impact, a purpose.

So many digitisation projects have been done to tick a box. But after that digitisation project was completed, they faced the dawning horror that work had only just begun. Even with the best technology, all of the objects will need to be re-photographed within the next decade (if not sooner). Digitisation isn’t a one off, it is a constant update.

Then the record online is looked at, and oh dear, it’s full of errors, typos, or has no useful information at all. So a team is hired to catalogue the record with meaningful data and fix glaring issues. And if the public have been leaving comments on the website about objects, of course that needs to be recorded too!

And when that project finishes (if it ever does), we learn that search engines need good tags so that the world can find that item. So it is back to the catalogued record to add SEO keywords. And when that project is finished, you have just caught up with the next thing on the horizon. So if you have already done all of the above, you are prepared for the facts that Adam Moriarty (Auckland War Memorial Museum) shares. Perhaps the most intriguing (horrifying) is that by 2020, 50% of all searches will be by voice.

“Back in the day when you jumped onto Google you got 10 results and you decided which one you wanted to choose. Now we have a system where the wealth of the world’s knowledge is out on the internet, but we are relying on a couple of devices or corporations to decide what is relevant and to package up an answer and deliver it to you.”

These voice operated systems (Alexa, Siri, etc.) prefer websites that structure the information in human readable language. For example, instead of a normal catalogued record:

Name: Guernica

Object Type: oil painting

Date Made: 1937

Artist: Pablo Picasso

These voice searches will prioritise entries that read “Guernica is an oil painting made by Pablo Picasso in 1937”.

This poses a dramatic re-envisioning of cataloguing an object. It is no longer just recording all of the facts about this item, but writing answers to questions people may ask. Which means hiring another team, to re-envision your database descriptions.

All of this work would provide unprecedented access to collections. But in many cases, technology changes are outstripping the pace that museums move at. Unless you have the budget and political capital that the larger museums have, it is almost impossible to fully revolutionise your collection data time and time again to make it fit the next thing.

So what does this mean for museums? Is it worth spending the time and money in these projects in the hope that it brings back that magical KPI – engagement?

Yes, but as Dave Sanderson said, do it with purpose. There is no need to do technology for technologies sake. Your organisation does not need to digitise, or 3D scan, or have the molecular breakdown of an object. What it needs to do is connect, educate, and protect the interest of the community it serves.

The role of museums is changing (or has already changed). No longer the sacred and flawless museum, with the silent halls of memory and curiosity cabinets. For better or worse, museums have opinions, and social policies to enact. Issues of inequality and social justice have found root in the marble floors of many GLAM foundations. No longer content to provide a passive retelling of the past, exhibitions and interactions are now curating voices previously unheard and targeting divisive issues.

This can be heard in the battle cry from Anasuya Sengupta and Adele Vrana to decolonise the internet. As cultural heritage institutions we need to acknowledge and then install the missing knowledge online, not just inside our walls.

The statistics they presented on Wikipedia were bleak:

1 in 10 Wikipedia editors are female or non-binary.

20% of the articles are written on or by people from the Global South.

14% of the world (North America and Europe) publish most of the knowledge.

Whether you like Wikipedia or not, there is no denying that it is a source of truth for almost all internet users. Those voice applications that Adam Moriarty mentioned, prioritise Wikipedia articles over museum websites, every time.

So these Wikipedia statistics are troubling. This vast collection of knowledge does not represent the diversity of five other continents, never mind immigrant populations. As cultural heritage organisations, we have a mandate to address this imbalance. To “begin the deeper process of reparation and healing for communities where colonisers purposefully and systematically destroyed their heritage (Adele Vrana).

And when we look at our organisations and consider our audience, Anasuya Sengupta and Adele Vrana posed these questions:

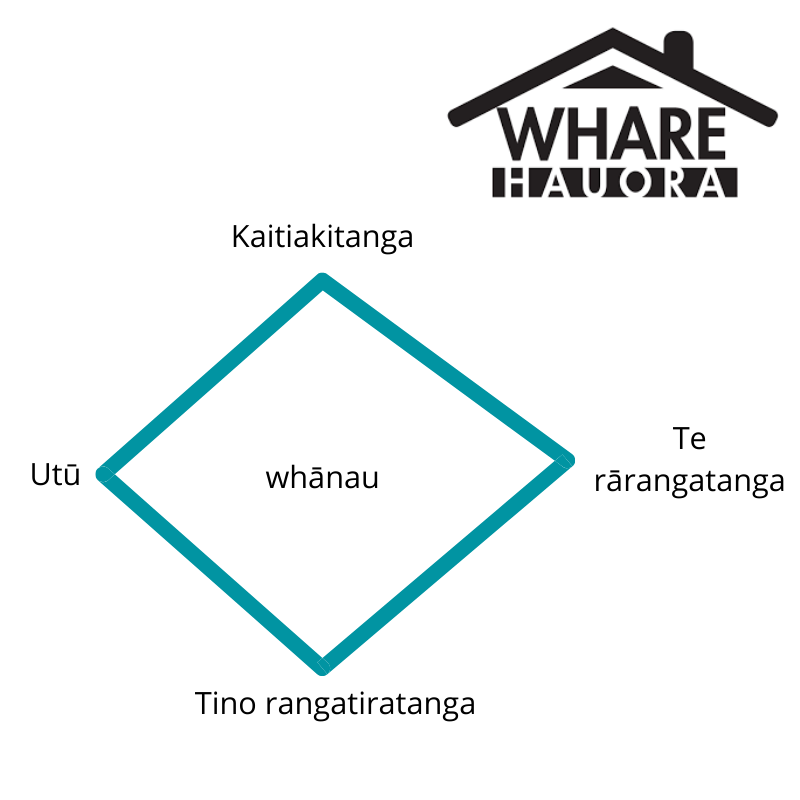

In essence, who do we serve? As Hīria Te Rangi from Whare Hauora points out, who is in the centre of your organisation’s decisions? For Whare Hauora, every decision made asks, is this in the best interest of the whānau or is it in the best interest of us?

GLAM institutions can apply a lot of the ethos of Whare Haurora to their own organisation. Imagine if all institutions could implement that same sense of selflessness, lack of presumption and arrogance, humbleness of spirit, and persistence in the face of overwhelming odds.

Their Pātiki, literally translated to flounder, revolves around this heart and care for the community.

Kaitiakitanga, we must take care of them

Te rārangatanga, an interweaving of people together

Tino rangatiratanga, give space and order for decisions to be made. This means independence to say no to the wrong choices.

Utū , compensation. Without the communities, there is no heritage and no audience. As Hīria rightly states, “you must give back”.

In the end, Hīria didn’t ask much of us …

That is the core of who we are. NDF wonderfully weaves discussions about technology and our responsibility together. The talks this year all demonstrated that technology is merely an aid for the transformation we see in the sector. That we are no longer about things, about dead histories. Now we are about people, and what concerns them, concerns us. They are the centre of our Pātiki.

Here is to the future.