The stunning setting of the Collins Barracks, National Museum of Ireland (Decorative Arts and History), Dublin, was the venue for the 2019 Natural Sciences Collections Association (NatSCA) conference. I was one of the trade exhibitors but also managed to participate in two tours, as well as sitting in on some of the interesting talks.

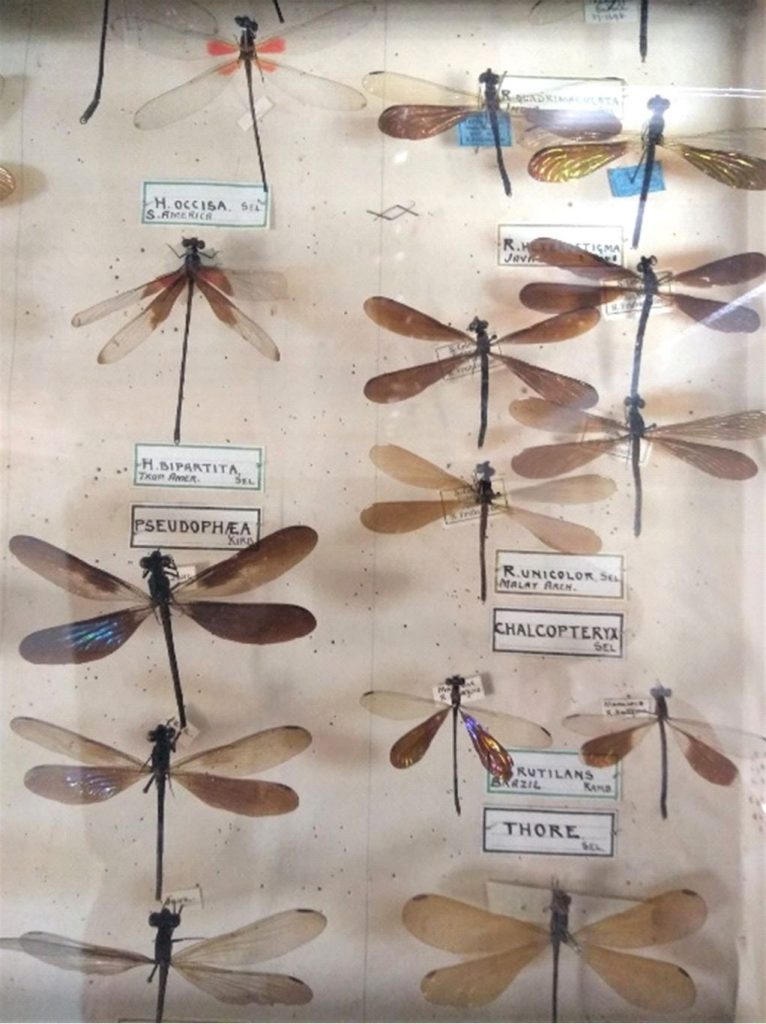

Day one commenced with a visit to the NMI‘s well-organized Collections Resources Centre in Swords where we were shown objects ranging from large taxidermy specimens to historic beetle collections.

A coach then took us to the National Botanic Gardens, Dublin. Blessed with warm, sunny weather, we enjoyed a tour of the gardens which included seeing the Great Palm House and an impressive reconstruction of an oak-framed and thatched Viking House. Our visit here was rounded off with a fascinating look at some of the dried and documented specimens held in the National Herbarium.

Ravenala Madagascariensis in the Great Palm House

On day two the conference proper started. I dipped into the afternoon section entitled‚ ‘Museums & Technology‘, since it was obviously the most appropriate subject from a Vernon point of view. This was composed of four talks:

Lee Davies, from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, spoke about Kew‘s aim to digitize and disseminate its collections. He admitted, however, that they are a long way from achieving that. They also have no integrated CMS at present.

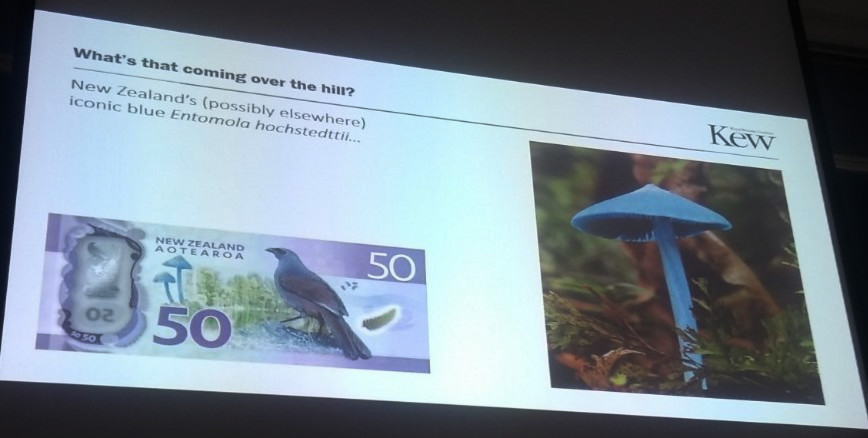

In discussing the limitations of taxonomy largely being based on morphology (which can sometimes be ‘horribly inadequate’, to use his words), Lee cited the examples where DNA sequencing has revealed what were previously thought to be one species are actually several closely related species that are morphologically very similar, such as the striking, blue mushroom, Entoloma hochstedtti. This appears on the New Zealand 50 dollar note – apparently the only country to feature fungi on their currency. This is one of the reasons why he wants curators to move towards sampling specimens for molecular analysis to become much more standard practice and widespread.

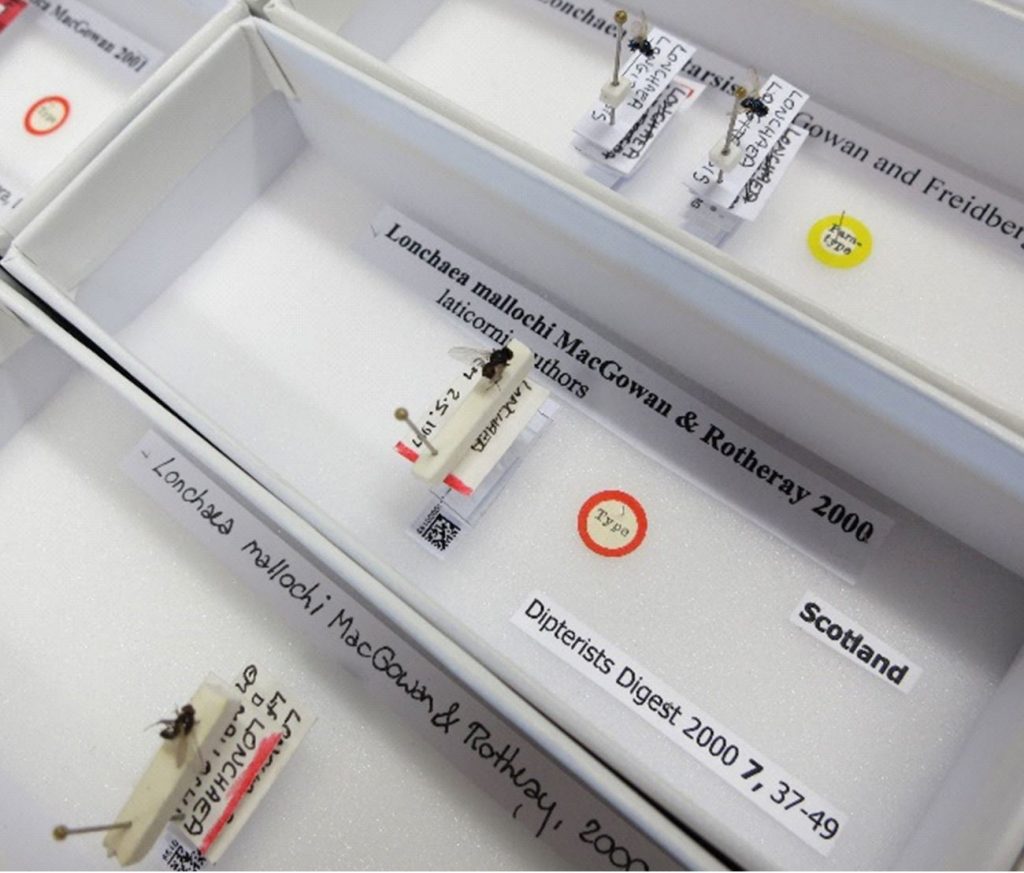

Ashleigh Whiffin from National Museums Scotland discussed, amongst other things, how the Lepidoptera type collection has been the first collection to be re-catalogued and re-housed. Historic labels have been photocopied, though these do not currently appear in the database (it is hoped they will do eventually). Specimens have been carefully rehoused in unit trays, together with QR codes which has greatly assisted information retrieval. They are currently trying out Earthcape, a biodiversity information platform which so far has made a favourable impression on them.

Clare Booth-Downs from the Royal Horticultural Society spoke about the Herbarium which has 88,000 dried specimens. The plan is to make these available online in the near future. Digitization was initially carried out using a flatbed scanner but it was found that this was not always suitable for thicker/bulkier material. A high resolution camera with an 80 megapixel back connected to an Apple Mac has now been employed, taking images at 600 dpi. This allows images to be enlarged in enough detail, without taking up too much storage space. During this process long lost items have been found, such as a potato sample collected by Charles Darwin.

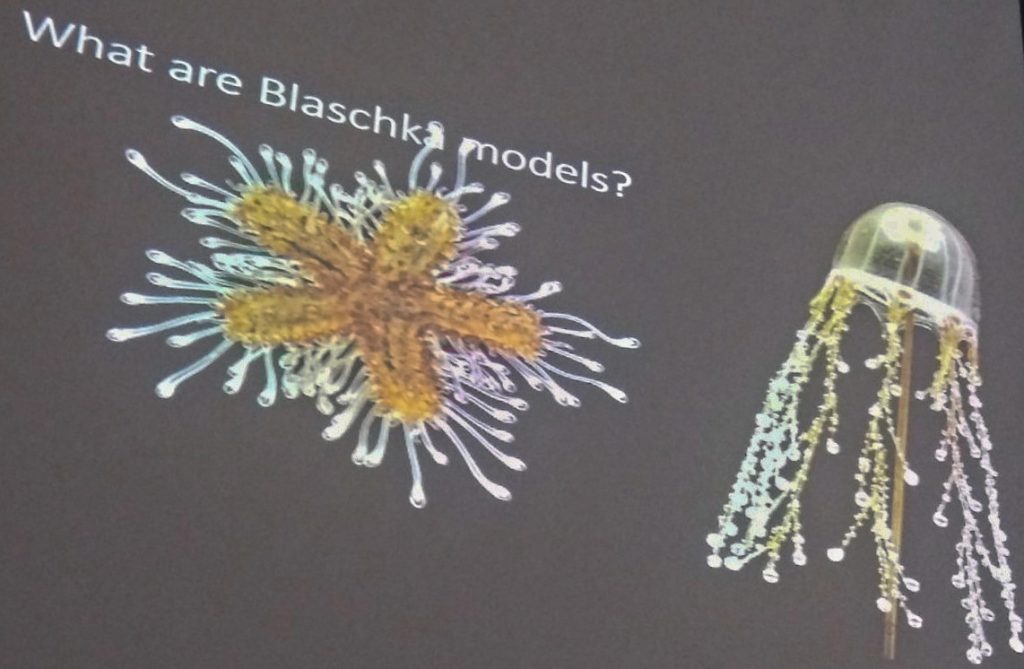

Emmanuel Reynaud from University College Dublin then rounded off this section of the conference by discussing the fascinating subject of Blaschka models. Leopold Blaschka, together with his son Rudolf, were glass artists based in Dresden, Germany. Active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they are famous for their invertebrate natural history models fashioned from glass, such as jellyfish, sea anemones and even sponges.

Emmanuel then discussed using the online Sketchfab platform to share 3D models of damaged instances of these delicate creations, as well as the use of back projection and hospital CT scanners to analyse both their composition and condition.

The conference then came to a close with a session on engagement which included talks ranging from the use of live arachnids alongside specimens in community engagement as a way of overcoming arachnophobia and the Brymbo Fossil Forest project in Wales, with its remarkable fossilized tree trunks.